Conceived during the Liberation of Paris, I grew up in the most beautiful city in the world. My parents looked forward to rebuilding their lives without forgetting their recent history.

As I had the good fortune to live Boulevard Saint Michel, in the heart of the Latin Quarter, I was sent to neighborhood schools and high schools, all a couple of blocks away and all, I would learn later, with a very impressive roster of past students.

For elementary and middle school, I attended the Lycée Montaigne. To me, going to school meant crossing the Jardins du Luxembourg by foot twice a day, all year ‘round. Karl Lagerfeld and Jean-Paul Sartre went to the Lycée Montaigne.

For high school, I was sent to the Lycée Louis Le Grand, founded in 1563, just a short walk through the halls of the Sorbonne. Famous alumnae compose an impressive list, from Molière to André Michelin, Edgar Degas to the Marquis de Lafayette, and Jean-Paul Sartre. These over-achievers did not help me get the required grades, but while at Louis Le Grand, I filed a patent for a video rear view mirror.

To have a second chance at finishing high school, I switched to the Lycée Henri IV, just behind the Pantheon. The Lycée Henri IV, founded in 1796, is a beautiful classic group of buildings and Alma Mater to the Duc d’Orleans, Baron Haussman, Simone Veil and Jean-Paul Sartre.

Finally equipped with my Baccalauréat, I joined the Ecole des Beaux-Arts to study architecture nine months before the student riots of May 1968.

The Ecole des Beaux-Arts is squeezed between the Boulevard Saint Germain and the Seine. The streets around are filled with galleries, cafés and art supply stores. As a rookie, I was confronted with classical charcoal drawing from a plaster model & the rendering of stone ornaments with a flawless wash of India ink. I took geometry but not much architecture yet. The school of architecture separated itself from the fine arts section, and we moved across the river to an aisle of the Grand Palais with a couple of other ateliers. At the time, an atelier was a school within a school, where the master dealt only with the grad students who, in turn would instruct the level just below them, and so on and so forth until the lesson trickled down to me.

Our professor was G.H. Pingusson, who belonged to the same architectural movement as Robert Mallet-Stevens and Le Corbusier. A famous project of his is the Mémorial des Martyrs de la Déportation. This very moving monument is set at the eastern point of the Ile de la Cité, in the shadow of Notre-Dame de Paris. I only met G.H. a couple of times in the two years I spent at the Beaux-Arts. One time being as he rode his bicycle backwards, sitting on the handle bars in the garden behind the Grand Palais.

And then I met somebody else. Late one evening, as I was alone in the atelier building a model of a futuristic chapel out of balsa wood, a student poked his head through the door and asked, “Do you want to go see Salvador Dali? He’s going to give a drawing lesson at some hotel. In twenty minutes.” I answered, “Sure. Who is he?” He didn’t know, but he said I should take a pad and get to this address now. So, I hopped on my Mobylette and got myself to the lobby of the Hotel Meurice on the rue de Rivoli. There, a small group of students were ushered into a huge salon decorated in gold leaf. We were asked to sit on the carpet. In front of us, was a clear inflatable sofa and an easel. There was a long wait. The master appeared, accompanied by two gorgeous women. He sat on the sofa.

As he started to talk, I wasn’t sure if he was speaking Spanish, French or something else. My mind wandered. I was trying to make sense of a situation that had none. I caught part of a phrase, and understood that were were about to learn how to draw “Le Cheval de la Mort” (The Horse of Death). Still sitting on the clear plastic sofa, he started to draw a multitude of overlapping circles, as he described the muscles and the tensions of a standing horse. We were instructed to copy on our pads as he drew. Then we were given, one by one, our crit. I do not, to this day, know what he said, but he added a few strokes to my drawing. When each crit was done, we were shown the exit. I met Salvador Dali, but still didn’t know who he was.

Around that time, it became clear to me that I was not to become an architect. Normal course of studies would take eight years, and, at my pace, it looked more like twenty.

I looked into commercial art, and more specifically, Advertising Design.

In the background, a song let me know of a place where there was a whole generation with a new explanation, and that appealed to me. Looking toward California, a college catalog at the American consulate library stuck out, that of Art Center College of Design in Los Angeles. It was all there: the professionalism and the palm trees.

The campus of Art Center College of Design was on Third Street in Los Angeles. It was the opposite of the Beaux-Arts: extremely structured, with a huge demand for immediate results, as well as encouragement for personal views. It took just a few days to dawn on me that I was not going to work in the metric system. The classes covered graphic design, advertising, type, film and photography. From my point of view, all of the students were foreign, British, Chinese, Texan, Californian.

All was new. All was possible.

I did the only thing there was to do: I got a cool studio down the street from the Hollywood sign, a 1959 Triumph TR3, and a girlfriend. In that order.

The curriculum was overwhelming. The instruction was invaluable. The teachers were L.A. admen, painters and car designers.

(Many years later, I was honored by being included in the school’s 2002 book, Design Impact.)

The high tuition encouraged me to skip summer breaks. I graduated early and fled immediately to New York to follow in the footsteps of George Lois and Bill Bernbach.

After shlepping my portfolio around Manhattan for a couple of months, I got a job as an assistant art director at Foote, Cone & Belding, then on the 36th floor of the Pan Am Building. I worked on Clairol, Schick, Frito-Lay: all brands that were new to me. But I was in advertising. In New York.

While at FCB, I had my second encounter with Salvador Dali. I knew who he was by then. I was buying supplies at Flax and noticed the tall, lanky figure dressed in a long black mink coat. Unmistakingly Dali. I greeted him, as if he were a visitor to my city, and reminded him of the Hotel Meurice class. We chatted briefly and wished each other good luck.

Foote Cone & Belding was great to me, but I got itchy for a new challenge and went to a smaller agency where I felt I would have more responsibilites. In retrospect, it was a mistake.

I saw the New York scene as too stressful, and started to look into going back to Paris where, I felt the industry was as fresh as New York had been a few years back.

I moved to Paris where I got a job as art director at TBWA, an agency created just a year before. It was a new breed of agency, where I felt creativity was the main concern.

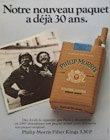

It was founded by Bill Tragos (American, Management), Claude Bonnange (French, Marketing), Uli Wiesendanger (Swiss, Creation), and Paolo Ajroldi (Italian, Client Services). The four had complementary specialties, and each a different nationality. The four shared the same office and that was the best part. They were creating campaigns that were fresh and intelligent. It was an exciting time. I worked on Lego, Antar, and Philip Morris.

Of course, I felt like flying on my own, and created an agency with my wife and my brother. We worked on various campaigns and created a line of personalized china; one could order a set of bistro plates with his name, the name of his country home, his boat, or any 14-character statement that came to mind. The product was a hit at the trade fair, “Moving Design.”

But still, I wanted to paint. I had to get my hands dirty. My wife and I rented a small studio space near The Bon Marché. I did illustration for

Le Monde, Maison de Marie-Claire, 100 Idées, the International Herald Tribune and too many ad agencies to mention. I contacted galleries both in Paris and abroad, where my work was included in several group shows. After school hours, we opened our studio for children to paint, draw and sculpt. We called it “L’Atelier de Gribouille.” The French children didn’t have much extra curricular activity in public school, so this was magical for the neighborhood kids and their parents. Some of the children made it all worthwhile.

I attended a new media presentation, and met an American in Paris making wild images for television and the entertainment industry. David Niles had a studio filled with the latest equipment, and when I visited, I discovered the potential of image manipulation. I became his assistant and art director, and we worked for all of the major French TV networks, created numerous commercials and music videos, and we covered the 1983 Tour de France for CBS Sports.

Our main tool was the FGS-4000 from Bosch that was one of the first production-ready 3D computer graphic systems. David and I were sent to Salt Lake City for a week of training on this machine and, as soon as we returned to Paris, we inundated the airwaves with flying logos.

In retrospect, the FGS-4000 was a very cumbersome tool, and even though we marveled at its possibilities, the results were crude by today’s standards. We were exhausted, but we were pioneers. I am grateful to David who allowed me to be part of his mad experiments.

With David, I created work for the television networks TF1, Antenne 2, Canal Plus and many others. We wanted to use our technology to fly the camera through the stripes of the TF1 logo. To visualize this animation, I built a model of the logo in plexiglas. We were educating ourselves and our clients in what was to come: 3D computer graphics.

To add to the excitement, in 1982, David got one of the first High Definition video set-ups from Sony (1124 lines), and again, I participated in the birth of a technology. It would take twenty years for that one to become mainstream.

After a few more years of freelance art direction, illustration and some painting, I was tempted to move on. A few gallery connections in New York and San Francisco convinced me that I had to return to the States. To California.

So we moved to the San Francisco Bay Area. Myself, my wife, our two children and a cat settled in Half Moon Bay.

I joined other Art Center alums at the Academy of Art College in San Francisco to teach Advertising Design classes. There, I was able to impart the importance of concept to rooms full of hopeful art directors and I enjoyed it.

An ad on the bulletin board at school caught my eye. Pacific Data Images was looking for an intern to test software they were developing. I spent a couple of months in front of a computer monitor, playing with software I did not know. There was no pressure to perform. When I got stuck, a few enthusiastic engineers huddled over me, excited about the path I had taken to get so stuck. Some of these enthusiasts are still at PDI/Dreamworks, at Pixar and Industrial Light & Magic. This internship was the beginning of a long ride making movies.

I loved becoming a part of this emerging field in the best place on earth for special effects in cinema. After my internship at PDI, I took my portfolio to Industrial, Light & Magic who hired me, a fine art painter, to train on their proprietary software. They told me it was easier to train an artist to work with technology than it would be to train an engineer to be a painter. Those were the days!

I have been at ILM for fifteen years, and I have worked on over thirty major features.

I painted a knight in the mouth of a talking dragon, a bunch of green Martians, a warty Jabba the Hutt, a hungry Spinosaurus, a cute Dobby, some hideous pirates, hairy wolves, naked vampires, a white scorpion, a beautiful snake, a smiling flower, two ice planet beasts, and an orange wind-up fish.

A surrealist shopping list.